Updated: April 2024

Motukiekie is a picturesque area on the Coast Road, halfway between Greymouth and Punakaiki on the West Coast. It is most well known for the Motukiekie Rocks, a group of iconic seastacks which have become a popular must-do shot for photographers.

The Motukiekie Shakedown is a landscape predator management project that has been evolving since 2010, targeting rats, stoats, possums, feral goats and feral cats.

It started as a small backyard project by me, Leon Dalziel, and has been driven on by the success of witnessing the birdlife quickly rebounding. In 2016, great spotted kiwi probe holes were found within the managed area. Further exploration in the hills above has identified more kiwi, and found small numbers of yellow-crowned parakeet, New Zealand falcon, South Island robin, rifleman, and most surprisingly, kea.

The Motukiekie Shakedown is unique in that it started as a one-man project, managing a comparatively large area that would traditionally have a sizeable volunteer community group behind it. The project continues to evolve and now employs Predator Control Rangers through a successful collaboration with Paparoa Wildlife Trust and the Rainy Creek Ecological Restoration Project – with project oversight from Zane Smith of Vation Limited, and support from Zak Shaw at Development West Coast.

There is an emphasis on exploring and using new technology, and basing decision making on research and measurable outcomes. I also have the luxury of physically living inside the management area, and being able to walk out the back door onto my tracks.

Stage One protected an area of 12 hectares, and Stage Two continues to expand to eventually protect an area of 800 hectares in the southwestern Paparoa Ranges.

The rarer bird species (kea, yellow-crowned parakeet, New Zealand falcon, South Island robin, rifleman, kaka) are only just holding on, limited to a small area above 250m altitude, probably due to heavy predation down lower.

Conservation Gains

Many threatened and at risk species occur within the management area:

| Species | Threat Classification |

|---|---|

| Kea | (Threatened – Nationally Endangered) |

| Great spotted kiwi | (Threatened – Nationally Vulnerable) |

| Blue duck* | (Threatened – Nationally Vulnerable) |

| Northern rata | (Threatened – Nationally Vulnerable) |

| Southern rata | (Threatened – Nationally Vulnerable) |

| South Island robin | (At Risk – Declining) |

| Blue penguin | (At Risk – Declining) |

| Fernbird | (At Risk – Declining) |

| Sooty shearwater | (At Risk – Declining) |

| New Zealand Pipit | (At Risk – Declining) |

| Red mistletoe | (At Risk – Declining) |

| Red-billed gull | (At Risk – Declining) |

| Variable oystercatcher | (At Risk – Recovering) |

| Kaka | (At Risk – Recovering) |

| New Zealand (bush) falcon | (At Risk – Recovering) |

| Fairy prion | (At Risk – Relict) |

Conservation gains include the preservation of genetic diversity in the existing birdlife, maintaining and expanding their current distribution, and the future goal of meeting up with another large-scale predator management project reasonably close by.

Opportunities exist for further investigation into bats, blue duck, invertebrates and various flora conservation, if their presence is found.

The Motukiekie Shakedown will add to land already under predator management, particularly in respect to Predator Free 2050 goals.

The project has the support of the Department of Conservation, West Coast Penguin Trust, Paparoa Wildlife Trust, and Te Runanga o Ngati Waewae.

Local residents are nature orientated and very supportive, particularly at the thought of having kiwis in their backyards, and once again enjoying the dawn chorus.

Motukiekie Rocks

The Motukiekie Shakedown will also protect the offshore Motukiekie Rocks – probably the largest cluster of unmodified sea stacks and islands on the West Coast, and home to fairy prion, spotted shag, red billed gull, blue penguin, southern black-backed gull, variable oystercatcher, and other seabirds.

The Motukiekie Rocks lie directly offshore from the management area, and will be protected from rat and stoat invasion from the mainland.

A survey in 1999 (D Neil) recorded seabird burrows on most of the eleven islands, with an estimated overall total of several hundred burrows. A fairy prion was found in a burrow, and it is likely that most or all of the burrows belong to this species.

Fauna Key Species

Birdlife

Bush birds currently present:

Great spotted kiwi, kea, bellbird, fantail, tui, weka, rifleman, fernbird, tomtit, New Zealand pigeon, yellow-crowned parakeet, New Zealand falcon, grey warbler, chaffinch, silvereye, blackbird, morepork, welcome swallow, Australasian harrier, South Island robin, shining cuckoo, house sparrow, song thrush, brown creeper, New Zealand Pipit, kaka.

Seabirds currently present:

Blue penguin, spotted shag, red billed gull, fairy prion, sooty shearwater, southern black-backed gull, variable oystercatcher.

Kaka (Nestor meridionalis)

Kaka are large, forest-dwelling parrots who can be found in a wide variety of native forest types including podocarp and beech forest. With probably fewer than 10,000 birds, the biggest threat to their survival are introduced mammalian predators, particularly the stoat, but also the brushtail possum. Kaka mainly breed in spring and summer, and nests are generally in tree cavities over 5 metres above the ground. In November 2017, a flock of six kaka were observed flying and calling over Motukiekie settlement northbound. In November 2019, a kaka was heard in the northern section of the management area, and in January 2020 two kaka were seen and heard near Firebase Cobra. It is not known if they are resident.

Sooty shearwater (Puffinus griseus)

A small number of sooty shearwater have been seen and heard circling above the 12 Mile bluffs and trig station A8NK, after dark and early morning, from early November to mid-February. Seabird calls were heard on the ground (possibly burrow calls), during the day on Whiteman’s Terrace in early December 2017, indicating that a population may still be nesting on the mainland. Historically, a colony of “seabirds” nested on the headland around trig station A8NK (locally known as “Starvation Point”), until they annoyed neighbours so much that the headland was burnt in the early 1940s.

Kea

Kea (Nestor notabilis) are endemic to the Southern Alps of New Zealand and are the world’s only mountain parrot. With only a few thousand birds remaining, the kea is a Nationally Endangered species. Territories are extensive and can cover up to 4kms² (Jackson, 1969; Elliott & Kemp, 1999). In January 2017, one kea was heard flying through the headwaters of Kararoa Creek. Anecdotal reports from hunters and possum trappers of hearing kea regularly in the same area since 2014, are encouraging.

In November 2017, a kea was observed close up sitting and calling on Mt George. In September 2018, a kea was seen flying and calling south of Mt George, southbound across the 10 Mile Creek. In October 2018 residents at Kararoa Creek reported hearing a kea in the watershed.

Roroa Great Spotted Kiwi

Roroa/great spotted kiwi (Apteryx maxima) inhabit c. 800,000 ha of remote, generally mountainous habitat in the top half of the South Island of New Zealand, where they form four genetically distinct populations: Northwest Nelson, Westport, Paparoa Range and Arthur’s Pass–Hurunui.

There are an estimated 14,000 roroa left in the wild, and the species is thought to be declining at a rate of 1.6% per annum across its range. Effective mustelid predator control has shown to lead to a 5.6% roroa population increase.

Roroa/great spotted kiwi (Apteryx maxima) species plan 2019–2029

In October 2016, kiwi beak probe holes were found, some only 40 meters from the Motukiekie settlement, and kiwi calls were heard. Subsequent monitoring has confirmed four kiwi pairs. This is very exciting news, especially after many years of anecdotal reports and speculation. Assuming a mean density of 1.5 pairs/km² (McLennan and McCann), there may be up to 12 pairs living within the management area.

*Whio Blue Duck

Historically, whio would have inhabited the Ten Mile Creek/Waianiwaniwa, a mountainous bush river flanking the eastern side of the Motukiekie Shakedown. It’s likely that a population remains in the mid to upper reaches, or that whio from the eastern side of the Paparoa Range have migrated back into the Ten Mile from the DOC whio program in the Moonlight Creek area.

Whio on the West Coast generally have quite large territories (~1-2km) and the Ten Mile Creek could sustain a couple of breeding pairs.

One blue duck was seen in the lower section of the 10 Mile Creek in March 2020 (misc. comms. DOC). A blue duck was observed by locals in nearly the same pool in the 1980s. Conversations with residents suggest there was an abundant population of whio in the 70s and 80s. Requires further investigation.

New Zealand long-tailed bat

Bats are New Zealand’s only native land mammal and is ranked as Nationally Critical. Chestnut brown in colour, they have small ears and weigh 8-11 grams. They are believed to produce only one offspring each year. They can fly at 60kph and have a very large home range (100km²). An aerial insectivore, they feed on small moths, midges, mosquitoes and beetles along bush edges. Female long-tailed bats congregate in maternity roosting trees with their young during the summer breeding season. They usually move roost tree every night.

Bats use dead and old trees with hollows and cavities to rest by day and breed in cavities in old-aged trees. They move to a new roost tree regularly so are not always present at a site, but may return later to reuse it. A social group can use over 100 different roosting trees.

“Bats require specific conditions: near a water source – creeks, gullies, streams. Open areas – forest edges. Big mature trees. Warm nights – November to April. Uses Magenta Bat 5 bat detector.” (Ben Paris, NZ Batman).

Flora Key Species

Celery pine (Phyllocladus alpinus), spider orchid (Singulary oblongus), northern rata (Metrosideros robusta) and southern rata (Metrosideros umbellate) and black beech (Fuscospora solandri). Small stands of black beech occur at Motukiekie, seemingly well outside its normal distribution range (Wardle 1969).

At altitude, there are large areas of yellow silver pine (Lepidothamnus intermedius), and in the forest there are many orchid species, including spider orchid (Corybas sp).

Red mistletoe (Peraxilla tetrapetala) has also been found which is classified as “At Risk – Declining”.

Pest weeds around the Motukiekie settlement include Elaeagnus, Wild ginger and bamboo.

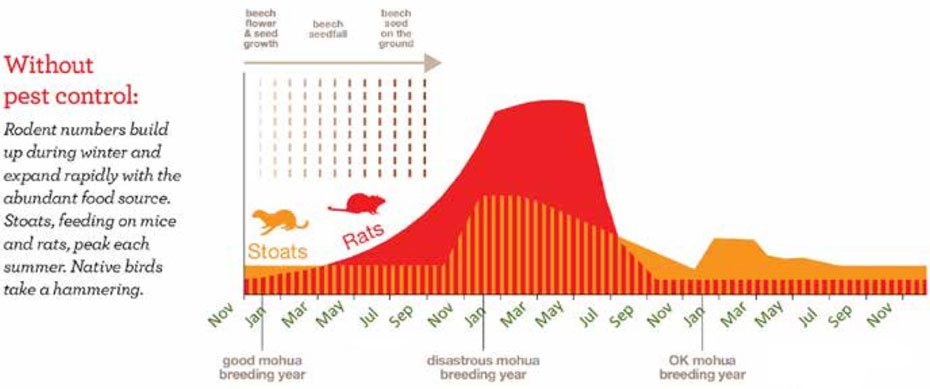

Predator plague cycle during a masting year

Predator Fun Facts

Ship rats (Rattus rattus), stoats (Mustela erminea) and possums (Trichosurus vulpecula) are the most significant predators present in Motukiekie, as well as the occasional feral cat.

Ship rats

Ship rats probably travelled to New Zealand on board European ships in the 1800s; they then spread through the North Island sometime after 1860 and through the South Island after 1890 (Atkinson 1973). Historically, ship rats, Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) and kiore (Rattus exulans) were all important predators of native wildlife; however, ship rats are currently by far the most widespread, common and significant of these three species of rat. They are also agile climbers and are ubiquitous in forests on mainland New Zealand, where they can reach plague numbers following beech (Lophozonia spp.) and rimu (Dacrydium cupressinum) mast events (Harper 2005; Innes 2005). As arboreal and omnivorous predators, ship rats prey on the eggs, nestlings and adults of native birds, as well as lizards, bats, frogs and land snails. They eat about 15g of dry food a night (10% of body weight).

Scarce in pure silver or mountain beech forest and very rare at high altitudes (above c.1000m asl). An agile and excellent climber, but a poor swimmer. Can spend considerable portions of time foraging up in trees.

Gestation 21-23 days, the litter size averaging 5-6. The young are mobile after 1 month and completely independent and sexually mature after three months. Females can produce three or more litters annually in a breeding season which can be 6-7 months or longer. Mortality rate is high, with few rats (<10%) surviving more than one year.

Home range is variable but usually between 0.5–4 ha (diameter of 100-200m) and densities can also vary widely but is on mainland sites usually 1–3 per hectare, though up to 6.2 per ha has been recorded. There can be substantial overlap in ranges of individuals within and between sexes.

Males range up to 300m (mean 194m), females up to 100m.

They know their neighbours well and if one is removed, invaders take over the empty range within days. In a study, the rats used 3-4 daytime nests over a 5 week period. Variable amounts of time are spent in each nest.

Stoats

Stoats were introduced to New Zealand in 1884 to control rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) (King & Murphy 2005), and are now ubiquitous in North and South Island forests and other habitats (Smith et al. 2007). Although stoats do not reach the same densities as ship rats, they are highly mobile with large home ranges and, unlike ship rats, are obligate predators rather than generalist omnivores (King & Murphy 2005). They are also semi-arboreal and capable of killing prey many times their own weight. Stoats hunt at any time, day or night.

A single litter is produced annually of up to 12 kits (mean 6–8), from late September (northern areas) to late October (cooler climes). Den sites are well hidden and changed frequently. Young are independent from early January. Nearly all females leaving their natal nest are already pregnant but delay development of the fertilised eggs until the following spring.

They have excellent powers of dispersal and individual juveniles have been known to travel over 70km in two weeks. They are also strong swimmers, known to have crossed water gaps of up to 1.1km to reach islands.

Main foods are rodents, birds, rabbits, hares, possums and insects, particularly weta. Lizards, freshwater crayfish, carrion, birds, eggs, hedgehogs and fish are also taken. Can eat 1/4 of their body weight a day.

Most stoats (>80%) live less than one year, but adult mortality is lower, and a few may reach 5–8 years of age.

Home range

Males often > 200 ha and females often > 100 ha. Although home ranges overlap, particularly between sexes (Erlinge & Sandell 1986; Murphy & Dowding 1994; 1995; Alterio 1998), it appears that many individual stoats have separate core ranges that do not overlap (Murphy and Dowding 1995; Young 1999).

Stoats tracked during the summer had very small home ranges (males 16.0 ha, females 9.4 ha), and with the exception of two immature animals, were defending intrasexual territories. Two males tracked in the spring had larger home ranges (47.9 ha) and were not territorial. (Cuthbert & Sommer 2002).

Density

Stoat density on Resolution Island (20,800 ha) in Fiordland, was estimated to be 1.4 stoats per km².

Alterio et al. (subm.) estimated absolute density of stoats in a South Island beech forest as 4.2 stoats km² (95% C. I., 2.9-7.7 stoats km²) for the summer period and 2.5 stoats km² (95% C. I., 2.1-3.5 stoats km²) for the winter period.

Original stoat density on Adele Island was about one per 9 ha before trapping was started.

“Stoats are shy of tunnels and devices”. “A dying rat is irresistible to a stoat”. “It is large populations of rats and mice that determine the number of stoats in an area”. “Stoats can’t survive long without mammalian prey. Rats, mice, possums and rabbits provide the most meat in their diet. If you remove them, stoats will eat a lot of birds over the short term, but they can’t maintain a large population long-term only on birds.” (Prof Carolyn (Kim) King 2016).

Possums

Brushtail possums were intentionally introduced to New Zealand to establish a fur trade and were successfully established by 1858 (Cowan 2005). They now occur throughout the main islands, although they have only recently colonised Northland and south western Fiordland. Like ship rats, possums are ubiquitous in forests, are agile climbers and can reach high densities (eg. 10–12/ha) (Cowan 2005). Although possums are primarily herbivorous, they opportunistically prey on native wildlife (Brown et al. 1993; Innes 1995; Sadleir 2000) and evidence of the impact of such predation on native species has increased dramatically in the last two decades (O’Donnell 1995; Montague 2000). Tennyson & Martinson (2006) suggested that possums possibly contributed to the extinction of South Island kōkako.

Stage One – Small-scale Trapping Program

✔ COMPLETE

Stage One was a small-scale trapping program of about 12 hectares primarily targeting stoats and rats, and occasionally possums. It was designed as a trial to test different traps and bait types, and see how labour-intensive a larger scale management project might be.

DOC200 humane kill trap boxes (weka-proof) were spaced at 100 meter intervals, interspaced with a TREX rat snap trap. The DOC200 traps were baited with a quartz rock replica egg, and a block of Erayz Dried Mustelid bait. TREX traps were baited with peanut butter, and then Nutella as a trial. Although Racumin (1st generation anticoagulant) was initially used to target rats, there are now no chemical toxins used.

Timms possum kill traps were mounted high on tree branches, or on a length of board placed on an angle against a tree, to keep them out of reach of resident weka.

Stage One was entirely self-funded to the cost of approximately $5,000 in materials, and 500 hours of labour ($12,500).

DOC Best Practice Guidelines

Rats – traps are placed in grids on tracks along 100 m contours at a spacing of 25–50 m to ensure that at least one trap occurs within each rat home range (refer to doc 2011a). Peanut butter is the most commonly used bait in snap traps and long-life lures are being developed for use in self-setting traps.

– one trap per hectare.

Stoats – traps are placed no more than 200 m apart on lines no more than 1 km apart, while making use of ridges, tracks, roads, contours and waterways (refer to doc 2013a).

– one trap per six hectares.

Possums – there is no DOC best practice for possum trapping, but the best practice for bait stations targeting possums recommends that they are placed no more than 150m apart, preferably on ridges and spurs, and along pasture boundaries (refer to doc 2011b).

Anecdotal Results

Birdlife has quickly returned to Motukiekie. It was interesting to witness the effects of predator management in such a small area (12 hectares). Most noticeably, blackbird, fern bird, grey warbler and tomtit are now regularly being observed around the inhabited settlement, when in 2010 they were virtually absent.

However, pest management within such a small area is extremely prone to predator re-invasion, particularly during a beech or podocarp mast.

Trapping data over the last few years hasn’t shown a noticeable decline, indicating that the 12 hectare managed area is being continually re-invaded, and too small to be effectively protected.

Conclusions from Stage One

Very labour intensive installing and checking DOC200 traps frequently

Lack of consistent advice on traps, baits and lures to use

Too small an area to protect from predator re-invasion

Needed a predator detection system independent of kill counts

Kill counts were satisfying, but how many didn’t get killed?

Needed bird monitoring and outcomes

Single kill traps are inefficient – resetting, multi-kill traps are the way forward

Shifted focus from ‘killing’ to ‘protecting’

DOC200 traps regarded as the accepted standard at the time

Trap boxes usually had to be handmade

My lack of understanding and experience at the outset

‘Everyone’s an expert’ especially backyard trappers

DOC200 traps not an option for a larger-scale one-man project

Stage Two – Going Large

> STARTED 2019

As time and funding allows, the Motukiekie Shakedown will continue to grow to protect a much larger area of 800 hectares.

Circles denote 200 Goodnature A24 traps at 100 meter spacings on a landscape stoat trap network. All traps are fitted 1 meter above the ground to exclude weka, and all traps above 250 meters in altitude are fitted with parrot excluders.

There is already an extensive network of tracks, routes and old coalmine roads within the area, requiring minimal preparation for traplines. Some time will be invested in further track-cutting and upgrading, although it is planned to extensively mark and GPS the traplines rather than cut them.

The Motukiekie Shakedown is registered with Predator Free NZ and uses the trap.nz online tool to record trapping data. Google Earth Pro, Garmin Basecamp, and QGIS software is used to analyse and plan traplines, along with a handheld Garmin GPSmap 62s in the field.

Goodnature A24 Stoat & Rat Traps

Patented self-resetting technology

Easy to install and maintain

Contains no toxins

Long-life lures for rats or stoats

Targeted and humane (A-Class rats and stoats)

Multi-award winning design

New Zealand designed and made

The A24 is a self-resetting multi-species kill trap. It was chosen because it is small, easy to install and resets itself after each humane kill up to 24 times per CO² canister. Goodnature traps kill instantly meaning no suffering and have been independently tested to meet the highest humane standards.

The Goodnature A24 traps are serviced once every six months with a new gas canister and ALP blood lure. This frequency may change to every four months going forward.

Traditional DOC200 box traps are bulky and heavy, and realistically require helicopter support to drop them into remote areas in a larger-scale predator management project. 20 Goodnature A24s will fit into a backpack.

TBfree aerial 1080 & ground control

August 2017

The south western flanks of the Paparoa Range, between Punakaiki and Dunollie (including Motukiekie), received a TBfree aerial 1080 treatment targeting possums in August 2017. Pot lines of cyanide was hand-laid as a buffer near the main highway and water supply creeks in December 2017.

This will suppress possum numbers for a number of years, and removes the requirement for targeting possums in the short term.

There will be a small secondary effect on rat and stoat numbers, however their populations bounce back reasonably quickly.

Hand-laid cyanide was repeated in November 2019 and August 2020.

December 2022

A second TBfree aerial 1080 treatment occurred in December 2022. It is not known whether regular further treatments will follow.

Monitoring birds and predators

Because stoats and rats killed by Goodnature traps will be scavenged, accurate kill counts are impossible to record.

Trail cameras and other systems will be used to monitor the presence and distribution of predators.

Bat monitoring to determine presence and distribution by deploying acoustic monitors around November each year.

Bi-annual forest and nocturnal bird monitoring to determine presence and distribution by deploying acoustic monitors around June and December each year.

Recent research suggests that motion-triggered cameras may be the most reliable detection method:

Al Glen captures predator portraits on camera

“For feral cats and mustelids, the recommended spacing is one camera every 500 metres”Capturing the cryptic – finding better ways to detect stoats

Using volunteers from Zooniverse to analyse the camera photos may be an option.

The Cacophony Project research and findings:

Zero Invasive Predators (ZIP) research and findings:

PAWS tracking tunnels – notifications, AI processing.

Camera Trap Monitoring

Browning Patriot trail game cameras are used to take close up photos of a Goodnature blood lure, as a method to determine a basic index of mice, rats, possums and stoats, and the presence of feral cats.

Multiple cameras and lures are left in the field for long term data collection with minimal maintenance. The monitoring may show trends over time.

The cameras are positioned 90-100cm from the lure and set to take three still photos at one second intervals when motion-activated.

A Goodnature blood lure is encased in a short section of drainpipe, with the lure held in place by two cut sections of pool foam noodle. The unit is covered with chicken wire to stop any nibbling by rats.

The distance between the camera and lure is being kept short so that small animals like mice set off the motion detection.

Future iterations may include:

ZIP MotoLure dispenser

Bluetooth or 4G cellular trail camera

Camera Trap Interactions per camera day – Motukiekie Valley

Forest and nocturnal bird monitoring

Acoustic recorders are being used to determine the presence and distribution of forest and nocturnal birds. AviaNZ software is being used to enable acoustic recordings of birdsong to be turned into reliable estimates of abundance.

Weka calls viewed in the AviaNZ spectrogram.

Longer term roadmap

Stage Three – rats and possums

It is acknowledged that all predators need to be suppressed within the system to achieve an increase in the bird population, and that suppressing one predator species can lead to an increase in the others.

Stage Three is intended to target rats and possums. Rat control may consist of aerial dropped biodegradable rat traps. Possum control may consist of bait stations and/or repeated ground control using leg hold and/or kill traps.

Stage Three may also include feral cat and goat control if their presence is found from trail camera monitoring.

Intensively managed ‘core areas’ distributed within a less-intensively managed matrix is also an interesting concept that will be explored.

Future Expansion

Future goals include expanding the Motukiekie Shakedown to meet up with the predator management work being done by the Paparoa Wildlife Trust. PWT is based in the hills behind Blackball, managing a large area on the eastern side of the Paparoa Range and specialises in great spotted kiwi management.

Reference Material

Stoats

Ship rat, stoat and possum control on mainland New Zealand

Kerry Brown, Graeme Elliott, John Innes and Josh Kemp, Department of Conservation, Te Papa Atawhai.

An overview of techniques, successes and challenges.

Stoat Control in New Zealand, Wildlife Management Report Number 108

Kay Griffiths, University of Otago.

A research report submitted in partial fulfilment of a Postgraduate Diploma in Wildlife Management.

Stoat control, kill trapping, best practice DOCDM-29448

Department of Conservation, Te Papa Atawhai. Unpublished.

Trap station layout, equipment, maintenance, lures.

Density estimates and detection models inform stoat (Mustela erminea) eradication on Resolution Island, New Zealand

R.I. Clayton, A.E. Byrom, D.P. Anderson, K-A. Edge, D. Gleeson, P. McMurtrie, and A. Veale

Ship rats

The home range of ship rats (Rattus rattus) in beech forest in the Eglinton Valley, Fiordland

Moira Pryde, Peter Dilks & Ian Fraser (2005).

A pilot study.

The next generation of rodent eradications: Innovative technologies and tools to improve species specificity and increase their feasibility on islands

K.J. Campbell et al

Special Issue Article: Tropical rat eradication.

Possums

Evaluation of five kill traps for effective capture and killing of Australian brushtail possums (Trichosurus vulpecula)

B Warburton, I Orchard (1996).

Five types of kill trap for possible use by professional possum trappers in New Zealand were tested for their potential to kill possums quickly and for their capture efficiency.

Great spotted kiwi

Summer home range size and population density of great spotted kiwi (Apteryx haastii) in the North Branch of the Hurunui River, New Zealand

Keye, C, Roschak, C, Ross J

Home range size, travel distances, and population density of the great spo ed kiwi (Apteryx haastii) were investigated in the North Branch of the Hurunui River.

A study of home ranges, movement and activity patterns of Great Spotted Kiwi (Ateryx haastii) in the Hurunui Region, South Island, New Zealand

Keye Constanze, Lincoln University

Kiwis for Kiwis Resources

Kiwis for kiwi, in partnership with the Department of Conservation, aims to bring together all New Zealanders as to save our national bird.

Kiwi (Apteryx spp.) Recovery Plan 2017–2027 (Draft)

Jennifer Germano, Jess Scrimgeour, Wendy Sporle, Rogan Colbourne, Arapata Reuben, Craig Gillies, Suzy Barlow, Isabel Castro, Kevin Hackwell, Michelle Impey, Joe Harawira and Hugh Robertson

Department of Conservation Threatened Species Recovery Plan

Genetic variability, distribution and abundance of great spotted kiwi (Apteryx haastii)

John McLennan and Tony McCann.

Misc

DoC tracking tunnel guide v2.5.2 DOCDM-1199768 DOC

Craig Gillies and Dale Williams. Department of Conservation, Te Papa Atawhai.

Using tracking tunnels to monitor rodents and mustelids.

Recovering Fiordland – Integrated pest control for biodiversity conservation (YouTube video)

Dr Graeme Elliott, Department of Conservation

Elliott speaks on the latest evidence for effective multi-pest management in southern New Zealand beech forest ecosystems.

The Ecology of Nothofagus Solandri

J Wardle, Forest and Range Experiment Station, Forest Research Institute, Rangiora

The distribution and relationship with other major forest and scrub species.

Taonga of an island nation: Saving New Zealand’s birds

Dr Jan Wright, The Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, May 2017

In a new report, the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment says New Zealand’s native birds are in a desperate situation.

Bats/pekapeka

Department of Conservation

Bats are New Zealand’s only native land mammals.

Goodnature Traps

Making Great Island great again

Press release 22 March 2017. DOC and Goodnature have deployed a network of self-resetting stoat traps on Great Island in Fiordland.

A24 vs Stoats – island eradication experiment deemed a success

September 2017 “This is the first stoat island eradication attempted with Goodnature A24 traps and was more successful than we could have hoped.”

Great Island A24 Stoat Eradication Project Update 01

The Great Island stoat eradication project was established by DOC with the objective to remove and defend the island from stoats using Goodnature A24 resetting stoat traps.

Self-resetting traps provide sustained, landscape-scale control of a rat plague in New Zealand

Anna Carter (Victoria University of Wellington), Darren Peters (New Zealand Department of Conservation)

Using A24 traps to keep rat numbers low – for good

Project Janzoon, Abel Tasman

Flying, biodegradable rat traps

Imagine a very small rat trap – about the size of a shuttlecock – that can be thrown from a helicopter or drone, that will then biodegrade once it’s done its job.

ZIP (Zero Invasive Predators) research and findings

Minimum fence height required to contain possums, rats and stoats

Assessing the Perth River (and Scone Creek) as a barrier to rats

Online Articles

The natural born killers lurking in our forests

Rebecca Macfie, 5 December, 2016, The Listener. “The tiny killers are still in their dens, suckling on mothers’ milk and primed for a season of slaughter.”

Hunting Kiwi – NZ Geographic, Issue 085, May–June 2007

Written by Sean Barnett. A year spent in search of kiwi among the ranges of the West Coast.

Capturing the cryptic – finding better ways to detect stoats

Kate Guthrie, Predator Free NZ. Des H. V. Smith and Kerry A. Weston.

Website links

Goodnature self-resetting traps

DOC Predator Free New Zealand 2050

Gotcha Black Trakka tracking tunnels

Echo Meter iPhone bat detector

Squark Squad trap notifications

The Cacophony Project birdsong and predator automated analysis

Discussion

Drones for GIS, aerial photography and videography, thermal surveying, trap data upload/download, visual trap checks, vegetation survey, asset inspection, payload delivery and recovery

Suppression success of rat numbers with current stoat trap layout

Third-party expansion on the Goodnature A24 trap platform (lure and accessories)

Autonomous surveillance and recording

Te Urewera Mainland Island – intensively managed ‘core areas’ distributed within a less-intensively managed matrix

Norbormide, Cholecalciferol paste (Feracol®) and cereal bait (Campaign®) for rat control

Bluetooth/wireless trail cameras + drones for photo upload

Ground-laid 1080 in bait stations or hand broadcast for rat control

Motukiekie Rocks predator and seabird (fairy prion) survey

Drone delivery and retrieval of acoustic recorders

ZIP Egg mayonnaise lure versus Goodnature blood lure

Wasp control with Vespex

Flexicoms – remote notifications network

CritterPic – photos of critters entering a unit

Motukiekie as a field-trial site

Predator proof fencing – eg. for sooty shearwater colony

Effectiveness of Ten Mile Creek/Waianiwaniwa as a barrier for predators